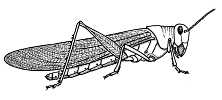

The Desert Locust

Mating. The male locust mounts the back of the female, applies the tip of his abdomen to hers and passes sperms into her reproductive tract. The sperms are stored in a sperm sac in the female's abdomen, and as the eggs pass down the oviduct during laying, the sperms are released and so fertilize the eggs.

Eggs. After mating, the female lays her eggs in warm, moist sand following a rainy spell. She pushes her abdomen down into the sand, extending the membranes between the segments, and burrowing to a depth of 50 or 60 mm. In this burrow, 50 to 100 eggs are laid and mixed with a frothy fluid, which hardens slightly and may help to maintain an air supply round the eggs. In 10 to 20 days depending on temperature and moisture, the eggs hatch and the nymphs make their way to the surface and emerge as ‘hoppers’ (like miniature adults but wingless at this stage).

Swarming. If food is in adequate supply and the hoppers are not forced to crowd together when they emerge from the eggs, the locusts live their lives separately as do other grasshoppers. If, however, the hoppers are crowded together for one reason or another, they enter a gregarious phase of activity. The hoppers tend to keep together in a band and move forward together. The crowding effect also results in a change of colour from the normal green, buff or brown to a striking black and yellow (or orange) coloration. There are also structural differences from the solitary form. The bands of hoppers vary in size from hundreds to millions, covering a few square metres or several square kilometres, depending partly on the age of the hoppers and how many bands have combined. As hoppers, they migrate only a few kilometres each day, basking in the early morning sun until their body temperature rises to a level which allows them to move off and eat all the vegetation in their path. When the temperature drops at night they climb bushes and plant stems and remain immobile.

After the final ecdysis, the adult locusts take to the wing and after a few days of short flights set off on extensive migrations, settling at night and in the middle of the day when it is hottest. A medium-sized swarm may contain a thousand million locusts and cover an area of 20 square kilometres. Such a swarm will consume some 3000 tonnes of vegetation per day; and so if a swarm lands on agricultural crops, the locusts will strip them of every vestige of leaf and edible stem.

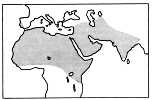

The swarms may travel many hundreds of kilometres from their place of origin, e.g. from Africa to India, and the females will lay eggs during their journey, so leaving the nucleus of successive swarms within a few weeks.

Methods of control. The range of the adult locusts is so great that international cooperation is essential for effective control. A swarm may originate in India but cause devastating damage to crops in Africa. Sixty countries in Asia and Africa are threatened by swarms of the desert locust.

The main method of control is by spreading poisoned bait, for example bran containing insecticide, in the path of the migrating bands of hoppers. The insecticide kills them by being eaten and by its contact with their bodies. Poisoned bait can be used only when the locality of the hoppers is known, and a careful watch must be kept over wide areas so that swarms are discovered as soon as possible after they emerge. The information is then sent to anti-locust centres, e.g. in Nairobi or London, and trucks and personnel are mobilized to take the bait to the appropriate location.

Other methods employed are to spray insecticides over swarms of hoppers or settled adults using aircraft or motor vehicles, or to spray the vegetation in the path of the hoppers. If the region of egg-laying is known, the vegetation in the area can be sprayed with an insecticide which kills the hoppers at their first meal. The danger with all spraying techniques is that the chemicals used may be poisonous to humans and other animals, particularly if used on food crops.

Two other species, the red locust and the migratory locust, have been held in check for many years by effective control measures, but the desert locust still constitutes a major threat. Constant vigilance and international cooperation are needed if crops are to be protected against this insect.

Currently it is being discussed whether the hazardous nature of the insecticides and the expense of spreading them is a cost effective way of controlling the desert locust. However, new and safer insecticides are being produced all the time and there is little doubt that farmers whose crops are threatened by locust plagues will want control measures to continue.

For illustrations to accompany this article see Insect Life-Cycles

| Search this site |

| Search the web |

© Copyright D G Mackean & Ian Mackean. All rights reserved.